One of our advisors, Alastair Robertson, set himself the challenge of understanding ‘Who were the 2nd Cohort of Nervians?’ Here’s what he found….

ON THE TRAIL OF THE 2nd COHORT OF NERVIANS

Alastair F. Robertson, October 2023.

INTRODUCTION

The 2nd Cohort of Nervians are the only named garrison of the Roman fort of Epiacum (Whitley Castle), that overlooks the River South Tyne in south west Northumberland. Their altar to the Sun God is now the emblem of Epiacum Heritage.

The Nervians were a Belgic tribe of German descent living east of the River Scheldt in central Belgium. Among the Belgic tribes the Nervians were regarded as the fiercest fighters, they opposed Caesar’s troops on three occasions, the first under their leader Boduognatus in 57BC, again in 54, and in 52 when an alliance of tribes was finally defeated, but only after the Romans had been sorely tried.1

SEGEDUNUM

It was probably in 71AD, when Quintus Petillius Cerialis was appointed governor, that the Second Cohort of Nervians arrived in Britain. The Cohort may have gone straight to Segedunum, now Wallsend, where it was the garrison until the early part of the second century.2

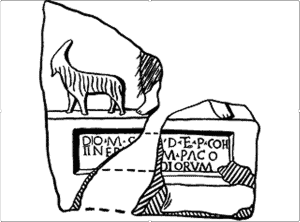

While at Segedunum the soldiers set up a statuette to Mercury (RIB 1303), the text of which reads;

“Deo M(ercurio) s[igil(lum)(?)] d(edicavit) et p(osuit) coh(ors) II Ner[vioru]m pago […]diorum”

Which translates as;

“To the god Mercury the Second Cohort of Nervians from the district of … dedicated and set up this statuette”

A military diploma of c.98AD, issued to soldiers who were honourably discharged after their term of 25 years’ service or more, listed among others the 2nd Cohort of Nervians.3 At some point, perhaps after Hadrian built his wall, the Cohort was posted to Vindolanda (Chesterholm).

VINDOLANDA

It seems that the 2nd Cohort was the garrison at Vindolanda for much of the 2nd century.4 The stump of an altar dedicated to the god Dolichenus (RIB Brit. 41.5), was found in 2009 by archaeologists digging inside his temple at the north end of the fort. The religion was secretive and may have been a forerunner to the Mithraic cult.

The text that can be deciphered reads;

“[…] […]ius V[2-3] [3] praefect[us] coh(ortis II Nervior(um)”

Which translates as;

“… […ius] V[…] prefect of the Second Cohort of Nervians.”

Interestingly, an altar to Mars (RIB 1691), was found in a garden wall near Vindolanda that recorded the presence of the third Cohort of Nervians;

“MARTI VICTORI COH III NERVORUM CVI PRAEEST T CANINIUS … MIIVS”

“To Mars Victor the Third Cohort of Nervians, under the command of Titus Caninius […] a vow fulfilled.”

The precise movements of the 2nd Cohort are unknown, but it was possibly from its base at Vindolanda that detachments were in evidence beyond the fort.

HIGH ROCHESTER

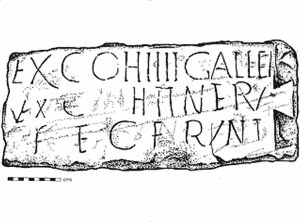

At High Rochester (Bremenium) a building stone (RIB 3491), found in a garden wall in 1982 recorded that;

“A detachment of the Fourth Cohort of Gauls and a detachment of the Second Cohort of Nervii made (this).”

It dates probably to latter part of 2nd century.5

HARDRIDING

RIB 1683 (Budge No.267) is an altar dedicated to the woodland god Cocidius that was found in June 1838 about one mile to the south of Vindolanda and is now in Chesters Museum.6

“DEO COCIDIO DECIMUS CAERELLIUS VICTOR PR COH II NER VSLM”

“To the God Cocidius, Decimus Caerellius Victor, prefect of the Second Cohort of Nervians, willingly and deservedly fulfilled his vow.”

The discovery was included the ‘Local Historian’s Table Book of Remarkable Occurrences’ in 1846;

“This year (1838) a Roman altar was found in the foundations of a house at Hardriding, a mile from Melkridge, on North Tyne, Northumberland: recording that Decimus Caius (the son of Arellius Victor) praefect of the second Cohort of the Nervii, in the free and due performance of a vow, dedicated this altar to the god Cocidius, who was synonymous with Mars. The period is that of Hadrian. It was presented to the Society of Antiquaries, Newcastle, by sir Thomas Clavering, bart.”7

Writing in 1961 Eric Birley believed that the altar was from a local shrine rather than from the fort of Vindolanda.

CARRAWBURGH

Altar RIB 1538 was found in 1874 at Carrawburgh (Brocolitia), and is also now at Chesters (Budge No.91). It reads;

“Genio hu(i)us loci Texand(ri) et Suve(vae?) vex(illarii) cohor(tis) II Nerviorum”

And translated;

“To the Genius of this place the Texabdri and Suvevae(?) members of a detachment from the Second Cohort of Nervians (set this up).”

Budge gives more information: “The Texander and Sunuci are said to have been peoples who were neighbours of the Nervii. This altar was found nearly in the middle of the station where it had been used as a building stone in the wall of an earlier Roman structure.”8

RISINGHAM

A detachment of an unknown Cohort of Nervians was at Risingham (Habitancum), where a well-executed building stone was found (RIB 1240).

“Vexil(latio) [coh(ortis) ..] [Nerv[ior(um)] fec[it]”

That is to say;

“A detachment (of the … Cohort) of Nervians built this.”

Unfortunately we’ll never know which one.

THE CHESTERS DIPLOMA

The famous Chesters (Cilurnum) bronze diploma, dated to 146AD (RIB 2401.10), found at the fort in 1879, lists alae and cohorts whose veterans had been honourably discharged. Part of the text reads;

“It is decreed that the cavalry and infantry in three alae and eleven cohorts, who have completed twenty-five campaigns, and who have obtained an honourable discharge, and who do not already possess them, shall have the rights of Roman citizenship …”

Included in Roman citizenship was the right of veterans to marry their ‘common-law wives,’ with whom they may have been living for years but, as soldiers, had been forbidden to marry. The list includes the Second and Sixth Cohorts of Nervii.9

EPIACUM

Perhaps it was after the Severan invasion of Scotland (208-211) and the subsequent withdrawal that the 2ndCohort of Nervians became the garrison at Epiacum (Whitley Castle); they were certainly present during the reign of Caracalla (211-217).

RIB 1202 was an inscribed slab in which a temple was dedicated to Emperor Caracalla by the Second Cohort of Nervians some time between 211 and 217 AD. Sadly it has long since been lost; it had gone even before Rev. John Horsley’s time, the first decades of the 1700s.

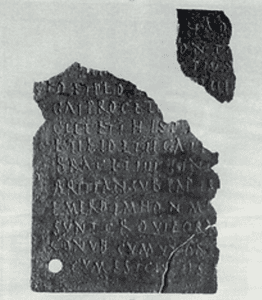

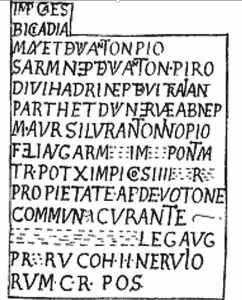

The lengthy inscription was seen and transcribed by Reginald Bainbrigg, a schoolmaster of Appleby, around 1601. Bainbrigg had a facsimile made of the stone, which itself has been lost for centuries. He sent his transcription to the great Elizabethan historian William Camden, who unfortunately altered the number of the cohort to fit his theory of the location of Roman forts across the north of England. He altered the second last line from ‘COH.II.NERVIO’ to ‘COH.III.NERVIO’. The fault remained unquestioned and it bamboozled antiquarians for over 200 years. The transcription, suitably amended, reads:

IMP. CAES. LUCII SEPTIMI SEVERI ARA

BICI. ADIABENICI PARTHICI

MAX. FIL. DIVI ANTONINI PII GERMANICI

SARMA. NEP. DIV..ANTONINI PII PRON

DIVI HADRIANI ABN DIVI TRAIANI

PARTH. ET DIVI NERVAE ADNEPOTI

M. AVRELIO ANTONIINO PIO

FEL. AVG. GERMANICO PONT. MAX.

TR. POT. .. X .. IMP. …. COS. IIII P.P…..

PRO PIETATE AEDE …. VOTO….

COMMUNI CVRANTE …….

………………. LEGATO AVG.

PR. …. COH II. NERVIO …..

RVM.. G.R. POS

“For the Emperor-Caesar, son of the deified Lucius Septimus Severus Pius Pertinax Augustus, conqueror of Arabia and Adiabene, Most Great Conqueror of Parthia, grandson of the deified Antoninus Pius, conqueror of Germany, conqueror of Sarmatia, great-grandson of Antoninus Pius, great-great-grandson of the deified Hadrian, great-great-great-grandson of the deified Trajan, conqueror of Parthia, and of the deified Nerva, Marcus Aurelius Antoninus Pius Felix Augustus, Most Great Conqueror of Parthia, Most Great Conqueror of …., pontifex maximus, in his 16th year of tribunician power, twice acclaimed Imperator, four times consul, father of his country, out of their joint duty and devotion, under the charge of Gaius Julius Marcus, imperial propraetorian legate, the Second Cohort of Nervians, Roman citizens, devoted to his deity and majesty, set this up.”

In this, the title of Caracalla and his father Severus are recorded at length and Horsley, who saw the facsimile, observed, “… if this temple has been erected to Caracalla, it has been dedicated to him as the genius of Rome, or of the Roman people; a flattering compliment too often paid to their emperors.” 10

Horsley recorded the fragment of an inscription slab (RIB 1203), which has also been lost, that had been built into the farmhouse at Castle Nook; not the present-day farmhouse beside the A689, but the original Castle Nook farmhouse up on the fort, where the Northumberland historian Rev. John Wallis was born in 1713. The dedication was similar in tone to the one above, praising Caracalla, from the same time but for a different building.11

“BRIT(annico) MAX(imo) GE[rm(anico) MAX(imo) PON]TIF(ici) MAX(imo) TRIB(unicia) P[ot(estate) XVIIII (?)] CO(n)S(uli) IIII P(atri) P(atriae) PR[oco(n)s(uli) …. PE[r] MILIT(es) CO[h(ortis) II NERV(iorum)] …”

Which, translated, reads;

“Most Great Conqueror of Britain, Most Great Conqueror of Germany, pontifex maximus, in his 19thyear of tribunician power, four times consul, father of his country, proconsul, [built this building] through the agency of the soldiers of the Second Cohort of Nervians …”

One of the most prominent items on display in the Roman section of the Great North – Hancock Museum in Newcastle is an altar from Epiacum (RIB 1198). A museum handbook gives the following description;

Altar found in 1837 at Whitley Castle fort (possibly the fort known to the Romans as Epiacum).

The altar is displayed with the very worn inscription facing the wall:

D[EO] APO[LLI]N[I] G[AIUS] / …………….IUS / ….. / ….. / COH(ORTIS) [II] NE[R(VIORUM)]…

“To the god Apollo Gaius …. of the Second Cohort of Nervians ….”

“The capital on the inscribed face shows the figure of Apollo Citharoedus with a plectrum in one hand and a harp at his left side resting on the ground. On the panel facing you there is a scene in which the central figure stands on a rock platform holding a sceptre in his right hand. He is flanked by two torchbearers who can tentatively be identified with Cautes and Cautopates and it would appear that her Apollo is equated with Mithras. The capital panel to your right has the figure of the Sun god wearing a radiate crown, with his right had raised and a whip in his left hand whilst on the left panel a bearded man in a tunic offers a cup in his right hand, having poured a libation to the figure standing on a platform opposite, from the jug at his left side. The figure on the platform is clothed in a tunic and carries a sceptre in his right hand. The suggestion is that Apollo is here being worshipped as Maponus.” (Maponus being a related native deity.)

“The altar, when found, was set in the socket of a large stone slab which in turn was supported by four stone pillars, each one a foot high. A coin was found on each of the top of the four columns, one of which (probably a coin of Faustina I, wife of Antoninus Pius) had been dated to AD 141-161.”

The sun god, who became Apollo, who became Mithras, is now well-known as the emblem of Epiacum Heritage.

And this, for all we know, is the end of the trail, the Second Cohort of Nervians may have remained at Epiacum until the end of the Roman occupation.

REFERENCES

1. Caesar, The Conquest of Gaul, Penguin Classics, 1956 Edition

2. Eric Birley, Research on Hadrian’s Wall, 1961, p.159, & David J. Breeze, Handbook to the Roman Wall, 14th Edition, 2006, p.131

3. Paul T. Bidwell, ‘Vindolanda’, 1985, p.32, & CIL (Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum) XIII.3606

4. Bidwell, p.31.

5. Bidwell, p.32

6. E.A. Wallis Budge, An Account of the Roman Antiquities preserved in the Museum at Chesters, 1903

7. Local Historian’s Table Book of Remarkable Occurrences, Vol. 5, edited by M.A. Richardson, 1846, p.72, quoting Rev. John Hodgson, History of Northumberland, Part II, Vol. III, 1840

8. Budge, several references

9. Budge, p.133-134, & The Handbook to the Roman Wall, 7th edition, J. Collingwood Bruce, Robert Blair, 1914, p.271

10. Rev. John Horsley, Britannia Romana, 1732, p.251

11. Horsley, p.250

SEE ALSO

Roman Inscriptions of Britain, online.

ILLUSTRATIONS

Colour photos of altars by the author, all other illustrations from RIB.